Zollie Kelman: The “Jewish Mafia Boss” of Montana

By Michael Portney

In the rugged landscape of Montana business history, few figures inspire as much intrigue as Zollie Kelman (1925-2008). A successful entrepreneur whose ventures spanned gaming machines, coin collecting, and casino operations, Kelman built a considerable legacy in Great Falls. Yet whispers have long followed his name—rumors of organized crime connections and mafia ties that persist even years after his death. As his own grandson would later reveal, Kelman himself would sometimes joke with a wink that he was "in the Jewish mafia," leaving family members and community observers to wonder where the truth ended and mythology began.

This exploration delves into the life, business dealings, and controversies surrounding Zollie Kelman, examining the evidence for and against his rumored connections to organized crime. Was he truly connected to figures like Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky, bringing their influence to Montana's gambling scene? Or was he simply a savvy businessman who leveraged a colorful reputation for protection and business advantage? The answers, like Kelman himself, prove more complex and nuanced than they first appear.

The Rise of Zollie Kelman in Montana Business

Born to immigrant parents on a boat sailing to the new world from Russia, Zollie Kelman made his mark in Montana through entrepreneurial vision and determination. His most notable business, the American Music Company, founded in the 1940s, provided jukeboxes, pinball machines, and other amusement devices to taverns across the state. At its height, the company operated approximately 700 machines in 61 establishments, making Kelman a significant figure in Montana's entertainment industry.

Kelman's business acumen extended beyond gaming machines. He developed a passion for coin collecting that resulted in the creation of the "Great Montana Collection," an impressive assemblage of U.S. silver dollars and paper currency. His collection method was brilliantly integrated with his business—he would sort through the proceeds from his gaming machines, setting aside coins with high silver content. This strategy led him to amass roughly 60,000 silver dollars and 6,000 Black Eagle Silver Certificates, establishing one of the most significant private collections in the region.

Legal Troubles and Allegations

Kelman's business activities, particularly those involving gaming machines, frequently brought him into conflict with Montana law enforcement. In 1987, state agents conducted raids on taverns hosting Kelman's gaming machines, resulting in a $50,000 fine. This wasn't his only brush with legal issues. According to press clippings, Kelman had been arrested for running an illegal pari-mutuel betting operation at horse races during the 1950 North Montana State Fair.

Further legal entanglements included a notable case involving L.R. Bretz, a disbarred attorney who alleged that Kelman and others had conspired to falsely accuse him of involvement in a 1976 burglary targeting Kelman's coin collection. While this lawsuit was ultimately dismissed for insufficient evidence, it highlighted the contentious nature of Kelman's business dealings.

The Montana Gambling Scene and Political Connections

The most compelling evidence suggesting possible organized crime connections comes not from direct mafia ties but from Kelman's methods of doing business and his extraordinary influence over Montana's legal and political landscape.

Attorney Steve Potts, who became Kelman's lawyer and close friend in the early 1990s, provided revealing insights into how Kelman navigated Montana's gambling laws. According to Potts, gambling was "clearly illegal in Montana in the 1970s except for bingo." However, Kelman found a creative workaround through a game called "Raven Keno."

"Someone came up with a keno machine that played a game called 'Raven Keno' and convinced Lewis and Clark County that it was really bingo," Potts explained. "Then the state attorney general issued an opinion stating that Raven Keno was illegal. The machine manufacturer sued the state in court for a ruling that Raven Keno was legal because it was really bingo. The courts agreed."

This legal victory came with a suspicious backstory. The Montana Supreme Court justice who authored the final opinion was Gene Daly, whom Potts described as "a not very smart attorney who had been the Cascade County Attorney and was friends with Zollie." According to Potts, "The judge (Gene Daly) who wrote the opinion was an old friend of Zollie. My impression of Gene Daly was that he didn't know much law, didn't care about that, and would have done anything he could to help Zollie and possibly other people involved in gambling. He was a 'good ol' boy.'"

With this favorable ruling in hand, Kelman seized the opportunity. "I was told that after the court opinion was issued, Zollie started building keno machines and had his employees stamp the figure of a raven on each one so if law enforcement tried to shut down the machines, he could point to the raven on the machine and the court decision which said Raven Keno was legal," Potts recalled, adding, "That's my idea of a great brand!"

Political Influence and Manipulation

Potts' account of Kelman's relationship with Judge Daly revealed even more about his methods of ensuring political protection:

"Zollie told me once that when Daly was the Cascade County Attorney, was running for reelection, and was being challenged by a Republican, Zollie found out that the challenger had gone to a whore house on Wire Mill Road in Black Eagle and paid for service with a check. Zollie got the check and met the challenger. He told the guy not to run too hard against Daly because if he did, the check would be made public. Daly won the election."

This anecdote demonstrates Kelman's willingness to use blackmail and leverage compromising information to protect his political allies—tactics historically associated with organized crime figures.

The connections went beyond just Judge Daly. According to Potts, "David Kelman had a company named Big Ten Electronics, which manufactured gambling machines, and which I believe Zollie had started. Daly was on the board of directors of the corporation (so was Tom Judge, a former Montana governor). All of the circumstances tell me Daly and Zollie were really close. Daly would have made sure that the court ruling was what Zollie and other gambling operators wanted."

These relationships with political figures, judges, and former governors suggest Kelman enjoyed extraordinary protection and influence—a hallmark of successful organized crime operations throughout American history.

The Mafia Reputation: Cultivated or Coincidental?

By the 1990s, Kelman had acquired a reputation in Great Falls that preceded him. As Potts admitted, "People thought he was a mobster. I was 31 years old, had heard those things, and was apprehensive." This perception was widespread enough that Potts initially approached his relationship with Kelman with caution.

However, Potts' personal experience with Kelman led him to a different conclusion: "I soon learned that despite his limited formal education, he was a brilliant, hard-working man who wouldn't hurt a flea. We became best friends and he had a huge impact on my life."

This contradiction between Kelman's reputation and his personal demeanor raises an intriguing possibility—one confirmed by Kelman's own grandson, who explained: "Growing up he would say he was in the Jewish mafia with a smile, but I was always told it was a rumor he let fester after the attempted robbery to keep the family safe."

This incident, referenced in multiple sources, occurred in 1976 when three masked intruders broke into Kelman's home, holding his family at gunpoint in an attempt to steal his valuable coin collection. Unbeknownst to the burglars, a family member managed to call the police from another room, leading to the arrest of the intruders and the safeguarding of the collection. Zollie was in such a rage he reportedly assaulted the handcuffed burglars by kicking them repeatedly while they were restrained on the ground, and was almost arrested himself as a result.

The trauma of this home invasion may have prompted Kelman to cultivate, or at least not discourage, rumors of mafia connections as a protective measure. As his grandson noted, this strategy would align with classic organized crime tactics where reputation alone could serve as a deterrent against future threats.

The Jewish Mafia Connection: Siegel and Lansky

Kelman's grandson provided perhaps the most direct statement linking his grandfather to organized crime influences: "I believe by all intents and purposes he was a racketeer influenced by Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky to bring gambling to the west."

This claim merits serious consideration within the historical context of Jewish organized crime in America. Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel and Meyer Lansky were among the most influential Jewish gangsters of the 20th century, instrumental in developing Las Vegas and expanding gambling operations throughout the western United States in the 1940s.

Siegel, famously responsible for building the Flamingo Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, represented organized crime's move into legitimate gambling enterprises. Meyer Lansky, often considered the "financial brain" of the mob, helped establish sophisticated money laundering operations and gambling networks across the country. Both men were part of what was sometimes called the "Jewish Mafia" or the "Kosher Nostra," operating in parallel and sometimes in cooperation with Italian mafia families.

If Kelman was indeed influenced by Siegel and Lansky's model, this would suggest he was replicating their approach of transforming illegal gambling into legitimate business through political influence, legal maneuvering, and strategic relationships with officials. The timeline aligns—Kelman founded American Music Company in the 1940s, the same period when Siegel and Lansky were pioneering organized gambling in the West.

Legal Maneuvering and Industry Influence

Potts' recollections indicate that Kelman wasn't merely operating within Montana's gambling laws—he was actively shaping them. "I heard that he was instrumental in lobbying the legislature to allow poker and keno machines. That was accomplished in 1985," Potts noted.

This timeline of Kelman's influence correlates with significant changes in Montana gambling legislation. According to multiple sources, Kelman played a key role in the gradual legitimization of gaming in Montana, moving from operating in legal gray areas to helping craft legislation that would benefit his business interests.

The 1985 legislation that legalized poker and keno machines represented a significant victory for Kelman and similar operators, transforming previously questionable activities into legitimate business ventures. This pattern—of illegal operations becoming legal through political influence—mirrors the larger trajectory of gambling in America, where figures like Siegel and Lansky helped transform Las Vegas from a desert outpost into a legitimate gambling mecca.

Business Disputes and Industry Control

The Kelman family's business dealings frequently involved disputes that ended up in court, suggesting an aggressive approach to protecting their gambling interests. Court records show that Kelman, through his company American Music Company (AMC), sued Dennis and Maeetta Higbee for breach of contract when they allegedly reduced AMC's share of profits and removed AMC's machines from their casino.

Another significant legal battle emerged over ownership of Nevada Sam's Casino, where Kelman claimed a 50% ownership interest, leading to litigation with Charles Henry and Allan Kosmerl. This dispute was settled in 1992, with Kelman's wife at the time acquiring a one-third ownership interest in the casino and related assets.

These legal maneuvers indicate Kelman was fiercely protective of his business territory and willing to use the courts to maintain control over his share of Montana's gambling industry—behavior consistent with someone operating with a territorial mindset common in organized enterprise.

The Next Generation: Family Legal Troubles

While Zollie Kelman's own legal issues were relatively contained, his son David encountered more serious problems with the law. According to reports, David Kelman was convicted in 1994 for failing to disclose the source of funds used to purchase a casino, resulting in the forfeiture of his interests in four gambling businesses. He was later found guilty of tampering with public records, a felony offense, in 1996.

These legal troubles in the second generation of the family business raise questions about the source of capital in the Kelman enterprises and the family's relationship with financial disclosure requirements—areas that historically presented challenges for businesses with connections to organized crime. Zolllie's daughter Abby Kelman-Portney recalled her father saying “You make more money in the gray area.”

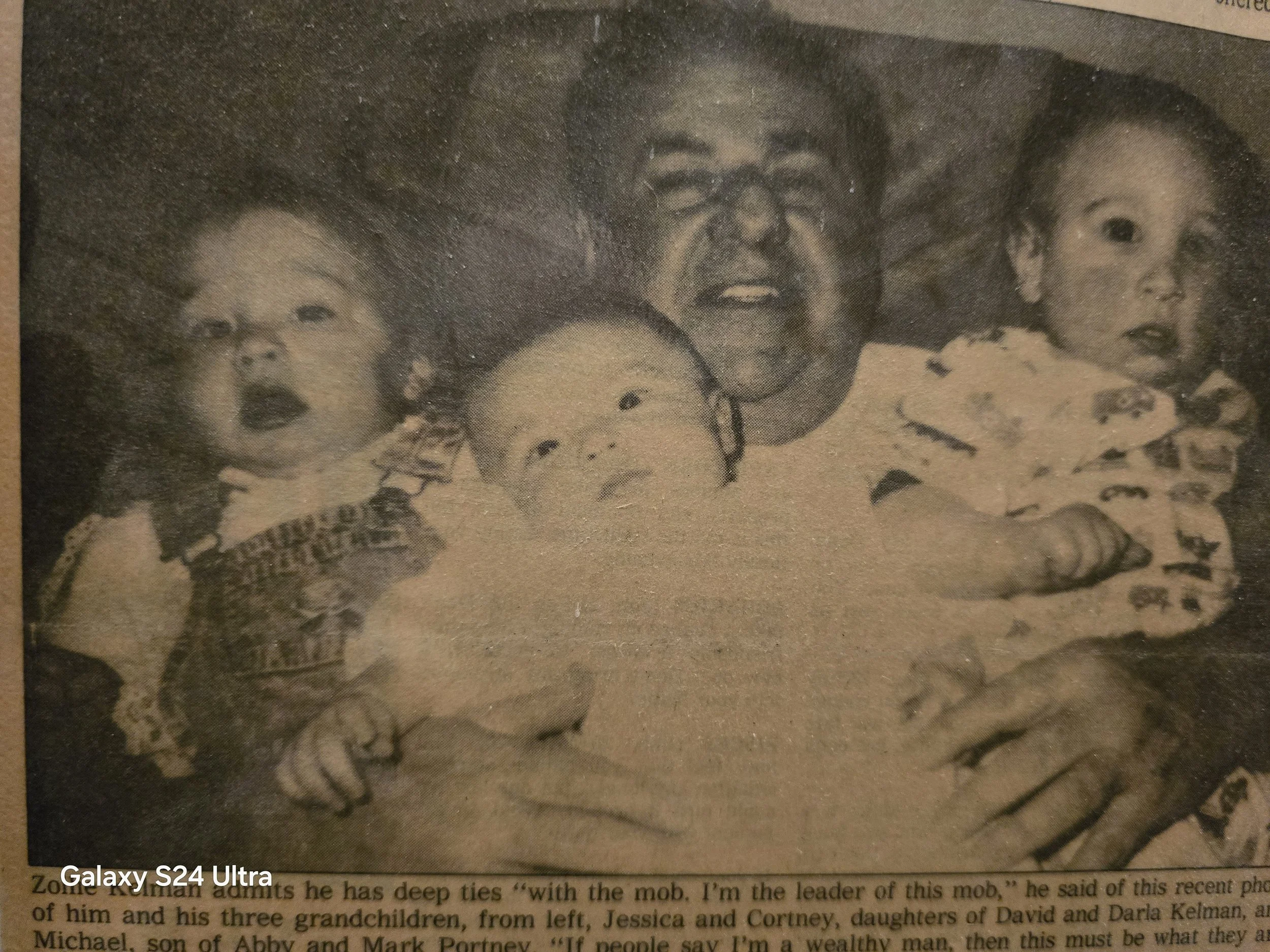

The Visual Evidence and Community Perception

On May 8th 1988, a front page article in Montana Parade newspaper pictured Zollie with his three oldest grandchildren. "I'm the leader of this mob,” he told the interviewer. Kelman had a sense of humor about his reputation. This kind of self-referential joke suggests he was aware of the rumors surrounding him and perhaps found them amusing or useful.

Community comments referencing mafia ties appeared when discussing the sale of his company, American Music Co., indicating that this perception extended beyond just family jokes to broader business community awareness. The persistence of these rumors even after his death in 2008 suggests they had become an inseparable part of his legacy in Great Falls.

The Australian Connection: International Suspicions

An intriguing chapter in the Kelman story emerged through his association with Larry Lippon, chairman and chief executive officer of Video Lottery Technologies Inc. According to Australian gambling regulators, Lippon's business associations with Kelman became a point of concern in their evaluation of Video Lottery Technologies.

The Victoria Gaming Commission in Australia removed Video Lottery Consultants from their list of approved suppliers, stating in their report that "VLC does not meet the requirements of honesty, integrity and repute... contemplate(d) for those who are to be (approved)." The commission's investigation focused partly on Lippon's business associations with Kelman, "who was convicted on charges stemming from illegal gambling."

This international dimension suggests Kelman's reputation and legal issues had implications beyond Montana, affecting business relationships across national boundaries. The Australian regulators' concerns about integrity and honesty connected to Kelman's influence indicate his reputation had real-world business consequences.

Distinguishing Organized Crime from Aggressive Business

When evaluating whether Kelman was truly connected to the "Jewish Mafia," it's essential to distinguish between organized crime membership and merely adopting similar business tactics. Many successful 20th-century businessmen operated in legally ambiguous areas, used political influence, and cultivated useful reputations without formal mob ties.

Several factors suggest Kelman operated more as an independent entrepreneur who employed tactics similar to organized crime rather than as a direct member of an established criminal network:

Local Focus: Kelman's operations remained primarily concentrated in Montana, without evident connections to larger national crime syndicates.

Legal Transition: He successfully transitioned his business from questionable legality to legitimate enterprise through lobbying and legal changes, rather than remaining in purely criminal activities.

Public Profile: Unlike many organized crime figures who avoided publicity, Kelman maintained a visible public presence as a businessman and collector.

Family Business: He established a family business that continued after his active involvement ended, suggesting a long-term business vision rather than short-term criminal profit-taking.

The Power of Perception and Strategic Ambiguity

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the Kelman story is how perception and reality blurred, creating a useful ambiguity that served his business interests. As his grandson noted, Kelman "let [rumors] fester after his family was robbed at gunpoint to keep the family safe."

This strategic use of reputation represents a sophisticated understanding of how perception can influence business outcomes. By neither confirming nor strongly denying mafia rumors, Kelman created an aura of protection around his enterprises while maintaining plausible deniability.

Steve Potts' evolution from being "apprehensive" about meeting the rumored "mobster" to becoming his close friend illustrates how Kelman's actual personality could disarm those who expected to meet a hardened criminal. This disconnect between reputation and personal demeanor provided Kelman with a unique advantage—the benefits of a feared reputation without necessarily engaging in the violent or overtly criminal behavior that typically accompanies organized crime.

Conclusion: Montana's Jewish Racketeer

Based on available evidence, Zollie Kelman most accurately fits the description provided by his own grandson—"a Jewish racketeer influenced by Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky to bring gambling to the west." This characterization acknowledges his aggressive business tactics, political influence, and legal maneuvering without necessarily claiming formal membership in an organized crime family.

Kelman operated in a historical context where the boundaries between aggressive entrepreneurship and organized crime were often blurred, particularly in the gambling industry. He appears to have studied and applied the business models pioneered by figures like Siegel and Lansky, who themselves were transitioning from overtly criminal activities to more legitimate business ventures.

The most compelling evidence of Kelman's methods comes from his extraordinary political influence—having a Supreme Court justice and former governor on his company board, using compromising information to influence elections, and successfully lobbying for legal changes that benefited his business interests. These tactics mirror those used by organized crime figures throughout American history.

Whether Kelman was formally connected to larger organized crime networks remains uncertain and perhaps ultimately unimportant. What's clear is that he operated with exceptional effectiveness in Montana's business landscape, using a combination of legal innovation, political relationships, and strategic reputation management to build a lasting business legacy.

In the end, the question "Was Zollie Kelman in the Jewish Mafia?" may be less relevant than understanding how he navigated the complex terrain between illegal and legal gambling in Montana, transforming questionable operations into legitimate businesses, and establishing a family enterprise that continued well beyond his lifetime. His story represents a fascinating case study in how reputation, business acumen, and political influence intersected in the development of Montana's gambling industry—regardless of whether that reputation was fully deserved or strategically cultivated.

As Steve Potts ultimately concluded after years of friendship with Kelman, he was "a brilliant, hard-working man who wouldn't hurt a flea," suggesting that behind the rumors and reputation was simply an exceptional businessman who understood the power of perception and wasn't above letting others believe he might be more dangerous than he actually was.

In the mythology of American business, particularly in industries with historical connections to organized crime like gambling, such strategic ambiguity has often proven to be a valuable business asset in itself—one that Zollie Kelman appears to have mastered throughout his remarkable career in Montana.

This article is based on historical records, family recollections, and legal documents. While every effort has been made to present accurate information, some details remain subject to different interpretations, reflecting the complex legacy of Zollie Kelman in Montana business history.